For the past seven years, Formula E has raced on city streets around the world, from Beijing back in 2014, all the way through to Berlin last month.

The 2020-21 season was the most competitive in the championship’s history, with Mercedes driver Nyck de Vries clinching the title by 7 points in the season deciding round.

The nature of the championship has presented challenges for North One Television and Aurora Media Worldwide, who produce Formula E’s television offering under the FE TV banner.

We caught up with the team in London to find out how the ExCeL facility came to fruition from a broadcasting perspective…

Influencing the circuit design

The London set up is unusual for the television production team, with their facilities laid out across multiple exhibition halls, something Sebastian Tiffert, who leads Formula E’s broadcasting department, describes as ‘luxury.’

“Normally, we’re doing an event in the city centre of Paris, in Rome, where there’s no space. Instead of rocking up with big TV trucks, everything is temporary and small.”

“We travel with multiple pods, built by Timeline. The pods carry all the technical equipment, sound desks, vision, and so on, around the world,” Tiffert explains.

“It gives us flexibility, as sometimes you must set them up around the corner or a u-shape. This [in London] is luxury for us, with everything in a nice line.”

The production layout reminded me of the World Rally Championship service park in Deeside, Wales, the series taking over multiple buildings within the Deeside Industrial Estate for the TV production and media to use.

Preparation for the ExCeL has been years in the making, The Race reporting that the ExCeL was Formula E’s ‘plan B’ option in early 2015, when the fate of the Battersea Park race was hanging on a knife edge.

One of the key considerations for West Gillett, Formula E’s television director, was ensuring that the contrast between the indoor and outdoor elements of the circuit was noticeable to the viewer watching at home.

While Gillett has no influence on the locations that series organisers choose, his team can influence the circuit design.

“The decision on which venue we’re going to is not something we would be involved in, but we get heavily involved in the track layout,” he tells me.

“Here, I did not want the indoor of the venue to look like outside. I didn’t want all the house lights; I didn’t want the cars coming in and for it to look like daylight.”

“The idea was to have that contrast between night and day, so indoors would be the equivalent of our Saudi race, a night race with the track lights. I’ve been really keen from the beginning to get that contrast.”

Gillett utilises the external camera angles to aid the transition: “Camera 17, you’re taking them indoors, visually the viewer knows now. If we look at the shot [see image below], you can see on the right-hand side it’s light and on the left-hand side its dark.”

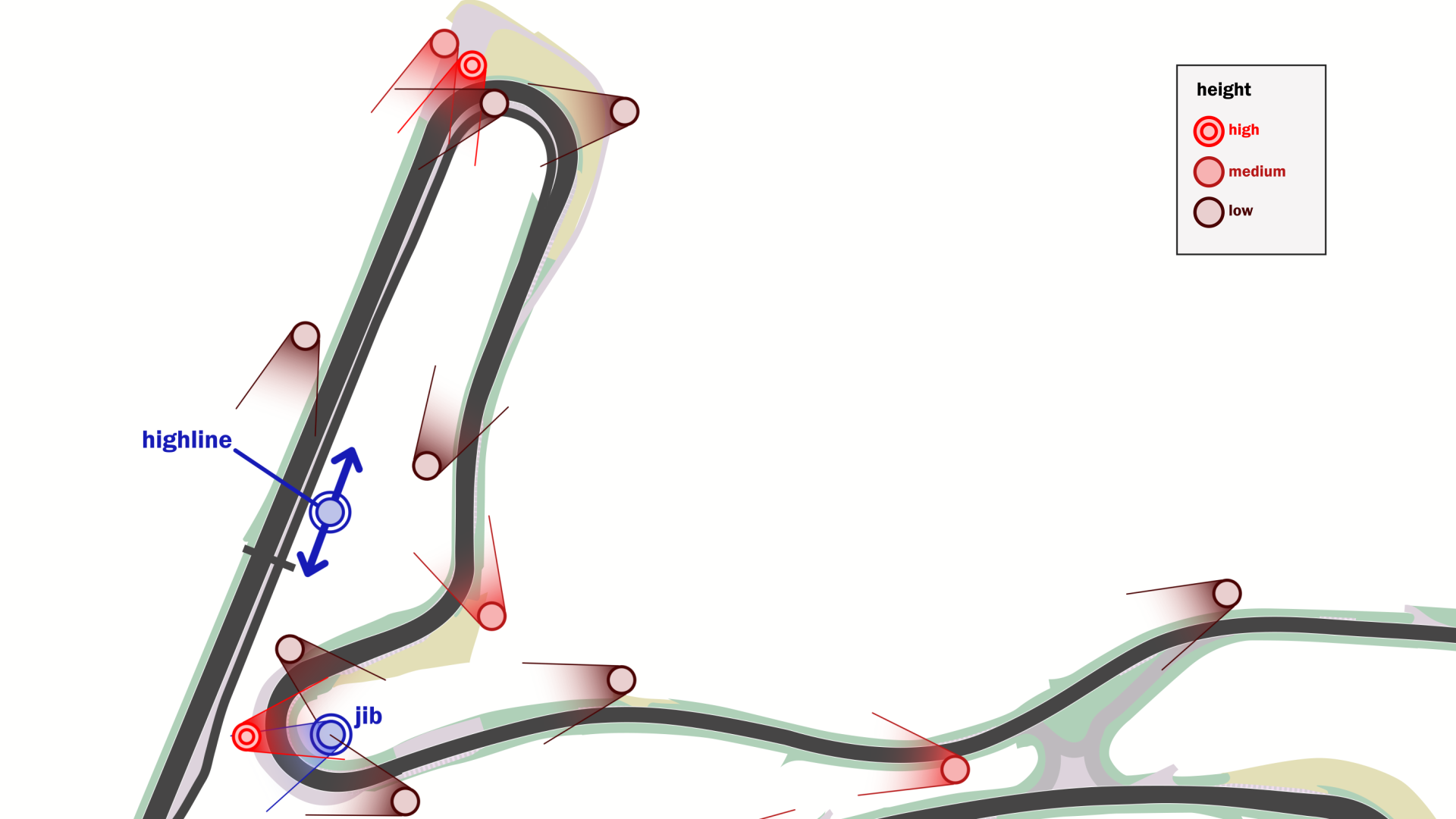

Also a factor for Gillett at all of Formula E’s venues is the location of the Attack Mode. Attack Mode gives drivers up to 8 minutes of additional power, the length varying from race-to-race.

To activate the boost, drivers must drive through the activation zone on circuit, which Gillett prefers to be in an area unlikely to feature much action during the race.

“I won’t want the Attack Mode down at corner where we expect there to be lots of overtaking, and then also we don’t want it too near the start.”

“A place that is quite difficult for us is Santiago, because I’ve got to show the Attack Mode and drivers coming down the start-finish straight to establish positions at the same time,” Gillett says.

“Ideally, the Attack Mode is half way around the track, with nothing else prior to it or after it that I need to show.”

Working within the ExCel confines

Living in London has been to Gillett’s benefit, having visited the venue multiple times in the run up to the E-Prix.

The indoor nature of the venue, plus the proximity of the ExCeL to the London City Airport, are obstacles that the team has had to work with from the outset.

“We came down a couple of years ago, and then again around six months ago [before the race],” he recalls.

“For us, it’s looking at the height of venue, the ceilings involved, the podium positions and cameras, making sure we could optimise the coverage inside the venue itself.”

“I was thinking about having a cable camera like we’ve had in the past, but the ceiling is just too low. There’s a lot of things like that that you just couldn’t do.”

“Another example is with the podium: we quite often have a jib camera for the podium, but because the space is really small, we can’t have the swinging jib.”

“Outside, we can’t have the helicopter live because we’re right next to the airport. It’s critically important to get that skyline and the relationship between the racing and the city itself,” Gillett believes.

“We did send a helicopter up on Friday to get some views for the pre-show to tie the London city to the venue, but we couldn’t do it live unfortunately.”

The build starts the week before the race, from the ground up, setting up all the infrastructure required to hold the E-Prix.

“We’re not coming to a venue which is pre cabled, like a football stadium,” Tiffert tells me. “We are starting on a white sheet of paper every time we go somewhere.”

“You need a crew which is very experienced in what we do, because you don’t have time to adapt. Certain things you can control when the track is finally finished, but the weekend goes so quick for us that you don’t have time to change on the spot.”

“Now, currently is a bit different because we have double-headers, we had a free practice session on Friday, so there’s a bit more space to, to improve and adjust things.”

Keeping the crew safe

The ExCeL is one of Formula E’s tighter venues, even by the electric series’ standards, with very little room for run-offs, making some corners dangerous for camera operators.

In some areas of the track, Formula E uses the Pan Bar system, as Gillett explains.

“Wherever there’s a TechPro barrier, I’ll have cameras that are using a new remote Pan Bar system,” he says.

“We anticipate that where the TechPro is, the wall could move up to three meters, so it unfortunately isn’t safe enough for a camera operator to be standing.”

“If I’ve got a head on shot, the camera operator is not standing there, there’s a camera head there and the lens.”

“The operator is standing five metres on the other side of that fence, in a completely safe location, operating with a Pan Bar system remotely.”

Gillett mounts cameras in unique locations to get the shot that he is looking for, something that is common for all street circuits that Formula E goes to, but more so with London.

“For example, we’ve mounted camera 4 up nice and high on a truss, allowing it to pan round and get the city skyline and the water.”

“With camera 17, the operator is in the basket of the cherry picker that’s mounted just over the fence. However, the cherry picker base is on the pavement below next to the canal.”

“There’s no room physically there to build a scaffold, because there’s a roof, and for other shots you’re up against the water. There are a lot of fiddly things like that, more machinery, more specialist camera equipment and remote heads to cover this event,” he says.

Reflecting on the first part of the weekend, Gillett was “quite happy” with how things had gone so far.

“Generally, I can visualise it [the camera positions] beforehand, I think that’s our skill set, I’ve been doing this for over 20 years, so can visualise it well. We’re in pretty good shape,” he believes.

“It’s rare that I change things when we’re on-site. I’m actually quite happy with this, I think the track coverage works quite well.”

“Obviously, I’m always trying to strive for getting as much speed, show the driving styles, show the rear of the car sliding, show the drivers racing, but also showing the cities.”

“It’s finding that balance between like wide shots and close up low action stuff.”

Gillett believes that the indoor section of the circuit will be even better once all COVID restrictions have lifted, hoping that a packed grandstand will add to the atmosphere.

Currently scheduled to begin in January, season 8 will take in 12 locations across 16 races, with new events in South Africa, China, Canada. The season finishes in August 2022, heading to South Korea for the inaugural Seoul E-Prix.

Contribute to the running costs of Motorsport Broadcasting by donating via PayPal. If you wish to reproduce the contents of this article in any form, please contact Motorsport Broadcasting in the first instance.